Kentucky

Old Growth Conference:

Installment

#1 - Going South to Kentucky

|

Robert

Leverett |

| Jun

29, 2007 07:30 PDT |

ENTS,

Monica and I have many

rich experiences to share with our fellow

and lady Ents that occurred during the June 13 – 24 period

when we were

in the South for the Kentucky old growth conference organized by

soooper

doooper Ent Dr. Neil Pederson. After the conference, we headed

to North

Carolina for a rendezvous with Will Blozan and Jess Riddle for a

special

Tsuga Search mission. It was as much spiritual as physical. On

leaving

Will’s, we returned home via the Blue Ridge Parkway – a

fully spiritual

experience. The full trip was planned so that my wife Monica

could see

and experience the mountains of my youth and hopefully fall in

love with

them (she did). But there is so much to relate that I must

present our

trip in installments. Here is the first.

|

| Field Trip at Blanton Forest,

Kentucky, Bob Leverett has his eyes on a red maple

that needs measured - photo by Carl Harting |

JUNE 13TH:

June 13th was a rainy day as Monica and I headed south. I had

high

expectations for the old growth conference in Kentucky and would

find

myself not in any way disappointed. We headed south on I91 then

west

across the Mass Turnpike (I90) crossing the Berkshires and part

of the Taconics. The crossing on I90 is ritualistic for me. I’ve done

it so

many times that I know all the trees by first name. On leaving

Massachusetts, we traversed a brief stretch of New York’s

Turnpike

before heading south on the rolling and ever pleasant Taconic

Parkway of

eastern New York. I immediately set about scanning the changing

landscape of trees for signs of an interesting species, the tree

of my

youth, the tuliptree. Beyond the conference, Tsuga Search, and

my usual

tree-measuring purposes, I had a special mission and that was to

take

note of the distribution of tuliptrees over the geographical

provinces

covered in the trip. I want to do my part in the study that my

HCC

colleague Professor Gary Beluzo is determined to refine the

distribution

maps for Liriodendron tulipifera. The tuliptree study will go on

through

the summer, and by autumn, hopefully, we’ll know more about

the

distribution of tuliptrees principally in Massachusetts and

northern New

York. We will also make plenty of comparisons of the performance

of that

noble species as it presents itself to adoring eyes in the

central

Atlantic states and the Southeast.

The first day of our trip was rainy and the poor driving

conditions

prevented me from snatching even quick glances at the wooded

landscape

that passed by. The day was spent driving with me fussing as

trucks

sprayed our windshield. It was just press the peddle to the

metal and

hope. We reined it in just north of the Virginia border in a

small West

Virginia town. The motel we stayed at was adequate and not

expensive, at

least not compared to Massachusetts standards, where highway

robbery is

the norm. However, the surrounding location of the West Virginia

spot

was suburban and carried none of the local color of the mountain

communities. It didn’t matter, we just wanted to rest.

JUNE 14th

Providence smiled on us and the weather turned favorable. We

rolled

down I81 with the lone line of the Blue Ridge Mountains to our

east and

the Alleghenies to our west. Basically, for much of its length

in

Pennsylvania and south, I81 follows a vast rift valley region,

which

bears different names in different geographical locations. In

Pennsylvania, we have the Lehigh Valley. In Virginia, we have

the

Shenandoah and Roanoke Valleys. Even farther south we encounter

the

Tennessee Valley. Mountains are ever present on both sides of

the valley

province, sometimes very close and sometimes more distant. Near

Roanoke,

VA, the Alleghenies to the west and the Blue Ridge to the east

are

joined for a brief distance. I’m unsure of the geological

explanation

for the brief disappearance of the valley.

In trips that I made

down I81 in the 1970s, most of the time the

driving was pleasant, but not anymore. Now one must dodge big

trucks and

suffer the negative visual impact of a degraded landscape. Much

of the

I81 corridor has become ugly with sprawling developments popping

up

everywhere. Alas, it is a sign of the times – perhaps

apocalyptic. As

for me, I long for the times when I81 was a delightful drive

that one

could take in early April and witness an explosion of color from

dogwoods and redbuds. Maybe a few folks even notices the gaudy

displays, but now, stressed out people drive 80MPH and yap incessantly on

cell

phones. You see them constantly multi-tasking in an extremely

dangerous

way, oblivious to the dwindling tidbits of a once natural

landscape that

zip by. But there is nothing that can be done. It is the

societal norm.

In southern

Virginia, we angled over toward the Kentucky border

and eventually picked up Route 160 that goes through a little

town named

Appalachia, VA. We crossed Black Mountain, actually a small

range of

mountains that contains Kentucky’s highest single point at

4,139 feet. Older elevations show up on maps as 4,145 feet – a fact of

little

importance to most people, but of critical significance to

people like

myself. Don’t ask me why. Unfortunately, Black Mountain is

privately

owned – the coal companies, of course. And they have done the

mountain

dirty. I will not digress into a rant about coal mining

companies.

Driving Route 160 is an experience. I don’t recommend it for

the

fainthearted. The road starts out benign enough. But as it gains

altitude, it turns narrow, has hairpin turns, and is extremely

steep. There are spots where the grade is at least 15% if not more. Our

car

labored mightily as I had to downshift into second gear. But 160

is

scenic and it had been honored by the name the “Trail of the

Lonesome

Pine”. The name honors John Fox Jr. who wrote a novel about

families in

the southern Appalachians in the early 1900s. A popular movie

was made

by that name. I vaguely remember the movie.

Dropping down Black Mountain’s west side, we headed through

coal mining

country and toward Pineville, Pine Mountain, and ultimately Pine

Mountain State Resort Park. That is where our conference was

held. Pine

Mountain isn’t as lofty as Black Mountain, but is nonetheless

steep-sided and is the site of Kentucky’s largest old-growth

forest. I

should point out that both Black Mountain and Pine Mountain are

geologically defined as mountains as opposed to the broad

Cumberland

Plateau, which has plenty of mountainous relief courtesy of

water

erosion. But according to what we were told, Pine and Black

Mountains

are the stubs of uplifts that have always born the shapes of

mountains.

|

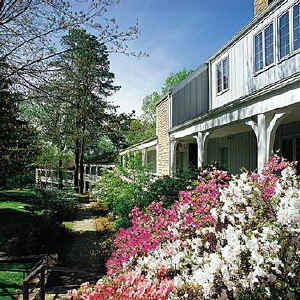

| Pine Mountain Resort Lodge |

In late afternoon, we made it to the resort and found it very

much to

our liking. The cabin we stayed in was well designed and most

comfortable. While checking in, we ran into Carl Harting and his

wife. It was great to see familiar faces. Ents are carpeting the

landscape.

Our cabin had two bedrooms, two baths, a living room area, a

kitchenette, and a back deck. It was immaculate. We shared the

cabin the

second night with our friend Lee Frelich.

Pine Mountain Resort

Park has a conference center, plenty of

hiking trails, a golf course, cabins, regular rooms, and a fine

restaurant. From the dining room, there are fabulous views of

the

surrounding mountainous terrain. Immediately down the ridge from

the

lodge is an old-growth forest named Hemlock Garden. You look out

the

restaurant window and down and into the old growth. Way cool!

Monica

gave a thumbs-up to everything and that made me extremely happy.

We

planned an early trip into Hemlock Garden for Friday morning

before the

conference.

Well, this ends the first installment and gets us ready for to

the real

goodies, which I’ll begin faithfully reporting on in

installment #2 next

week.

Bob

Robert T. Leverett

Cofounder, Eastern Native Tree Society

|

Kentucky

Old Growth Conference:

Installment

#2 |

dbhg-@comcast.net |

|

Jun

30, 2007 18:38 PDT |

ENTS,

This is installment #2 of Monica and Bob's trip taken during the

period of June 13th-24th. The first installment covered the 13th

and 14th. This covers the 15th, the first day of the Kentucky OG

conference.

JUNE 15th

On

June 15th, Monica and I awoke in the cabin to clear skies and

empty stomachs. However, the morning was cool and so I took a

quick walk around the cabin to check out the forest while Monica

showered. I found a short trail and took it. I noticed the

abundance of hickories, black and white oak, American beech, and

tuliptree. They were commingled. There was a lot of poison ivy,

both on the boundaries of the woodlands and within. I tiptoed

around it to take a girth measurement of a black oak. Tree

heights were around 100 feet. I searched for taller stuff, but

then my stomach growled. It was time to put on the feed bag, so

I hustled back to the cabin. Monica was ready. Our plan was to

satisfy our hunger at the lodge before heading down the trail to

Hemlock Gardens. We were mindful that the day was going to be

hot and humid, so we rushed a bit, but not too much. I always

look forward to breakfasts in the South. I love New England, but

breakfasts are not a specialty in the

Northeast. There are the good spots, but they are rare. However,

good breakfasts in the South are common. Spiced sausage, fresh

eggs, bacon that you can’t see through, country ham, biscuits,

gravy, and grits are the mainstay. Umm, umm good! Unfortunately,

I have had to give up country ham because of the excessive salt

content. You can permanently preserve your internal organs with

a daily ration of country ham, if consumed continuously for a

couple of decades.

| Hemlock Garden Trail

|

Length: .5 mile loop

(1 mile with Inspiration Point spur); Elevation Change:

250 feet

Description: The path descends down into a wooded

ravine containing old-growth hemlock trees that are 3-4

feet in diameter and over 300 years old; the Hemlock

Garden. Many large white oak and tulip poplar trees are

also found here and several large sandstone boulders

form Boulder Alley, where the trail meanders along a

woodland stream among house-sized rocks. Other

highlights include footbridges, cascading stream views

and a charming native stone shelter house built by the

Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930’s. An optional

side-spur path leads to Inspiration Point, a large

thicket of rhododendron nestled among towering hemlocks. |

The

Hemlock Gardens trail drops rapidly down into a steep ravine.

The trail then winds a bit, before eventually reaching an old

CCCs shelter, which was constructed in the 1930s. The change in

elevation is a little over 250 feet, so the climb is quite

modest. A stream flows through the ravine, providing extra

moisture for a number of charismatic tree species. Big leaf

magnolia, umbrella magnolia, and cucumber magnolia are all

present in the Ravine as is tuliptree, black gum, hemlock, red,

black, white, and chestnut oak. The red maple, sugar maple,

pignut hickory, white ash, yellow and black birch and American

beech combined with the former list remind one that the Kentucky

woodlands are a mix of northern and southern species jumbled

together. It is a mix and match theme that is repeated through

the southern Appalachians. The Smokies have it in spades, but so

do the mountain woodlands of eastern Kentucky.

Hemlock Gardens is old growth and the question always arises in

the inquiring mind as to why? Layered sedimentary rock, a

sandstone conglomerate, creates overhangs that obviously

deterred logging, but only within a narrow corridor; basically,

the bottom of the ravine. I should point out that rhododendron

and mountain laurel are common in eastern Kentucky and these

evergreen shrubs impart a slightly exotic look and feel to the

vegetation. They can do it singly, but in combination one feels

transported beyond the temperate zone.

Adelgid

has reached the hemlocks and the Nature Preserves people who

manage the site plan to hit the adelgid with everything they

have. It is a refreshing attitude. They value not only hemlock

habitat, but individual trees. That doesn’t always happen. The

staff has an abundant supply of Merit, courtesy of the nearby

golf course, so I’m happy to report that the hemlocks of

Hemlock Gardens have a reasonably bright future.

I

measured a number of trees on our quick rounds of the trail, a

sufficient number to convince me that the tallest trees are

hemlocks and tuliptrees and are in the mid-120s with the

exception of a single tuliptree that tipped the scales at 131.1

feet in height and 9.8 feet in girth. The best I could do on

hemlocks was a respectable 124.7 feet in height and 7.1 feet in

girth. A few hemlocks approach 12 feet in circumference as a

consequence of heavy buttressing because of being on a steep

slope. A single chestnut oak in Hemlock Gardens reaches 101.2

feet in height and 12.2 feet in girth. It is the largest tree we

saw. With some searching, I think we could establish a Rucker

index of around 110 for Hemlock Gardens. On 7 species, I got

111.2. Notably, size of the hardwoods was not appreciably

different from what I routinely see in the Massachusetts

Berkshires and Taconics and the hemlocks of Hemlock Gardens are

comparable to their old-growth Berkshire counterparts.

All in all, Hemlock Gardens is fairly impressive, especially

when one combines forests with rock outcroppings. Most

importantly, the site provided Monica with her first real look

at a southern Appalachian forest – a mixed mesophytic forest.

The rhododendron and mountain laurel gives Hemlock Gardens that

exotic, southern Appalachian cove forest look, but in a fairly

mild dose within Hemlock Gardens. I knew what Monica had ahead

of her in the Smokies and so I was careful not to spoil the

ambience by uttering one of my silly Bubba-like statement such

as “You ain’t seen nuthin yet!”.

In summary, Hemlock Gardens is a fairly dry ravine environment

with moderately large, quite old, and somewhat tall trees.

Although the Gardens is located in the wettest area of the

state, which I presume averages around 50 to 55 inches of

precipitation annually, the abundance of oaks in the ravine on

the slopes just above the wet corridor speaks to less

precipitation--I’m guessing between 40 and 45. One last

statement of our round of the Gardens, I wish they had chosen a

different name. “Gardens” sounds too manicured, and

manicured, it isn’t.

Upon

returning from the walk, we prepared ourselves for the start of

the OG conference. We met some old friends of mine, ate a

delightful lunch at the lodge, and then filed into the

conference room, ready for what we all knew would be a

delightful experience. I’ll save the conference for

installment #3.

Bob

|

| Installment

#3 |

dbhg-@comcast.net |

| Jul

11, 2007 15:01 PDT |

ENTS,

This is Installment #3.

The Kentucky OG conference commenced on June 15th at 1:00PM at

Pine Mountain State Resort Park. The conference accommodations

were absolutely top flight. We were all set to go. Our EKU host

and faithful Ent Neil Pederson started the conference by giving

us a preview of what was to follow. He then introduced yours

truly for the first presentation. I had put together a

PowerPoint Presentation with a mix of text and old growth images

that was supposed to provide an overview, past and present, of

old growth awareness from several perspectives. In the prior

weeks, I had struggled to find a balance between presenting the

historical roots of old growth awareness as it emanated from:

(1) early naturalists, (2) past forestry efforts in inventorying

property being acquired by the then fledgling U.S. Forest

Service, a nd (3) the later efforts of naturalists, scientists,

and forest activists often attempting to preserve forests. I

interjected my personal journey through my developing state of

OG awareness. I pointed out how slippery the slope becomes when

we attempt to institutionalize an elusive state of forest

development. Looking back, I'm unsure if I accomplished anything

with my presentation, but it was early and we were all in high

spirits so I think I squeaked through in a more or less

ceremonial role. The real presentations were about to begin. But

before leaving the theme of my presentation, a later

presentation by my long time friend Rob Messick of North

Carolina concentrated on the state of knowledge and awareness of

prior forest researchers. Rob has specialized in this avenue of

research and some of his material is illuminating.

Following my presentation, Ryan McEwan gave a fascinating

account of the “Dendroecology of Ancient Oak-Ash Woodlands in

the Blue Grass Region of Central Kentucky”. Growth rates and

forms of the bur oak that once dotted the Blue Grass domain

immediately caught my attention. Basically, McEwan argued that

early Native American and later colonial land use accounts for

much of what we attribute to natural processes to include the

Blue Grass that early settlers saw. Small Pox had eliminated

much of the Native population, and for a time, Kentucky became a

unclaimed hunting grounds for tribes such as the Shawnee, Miami,

and to an extent, Cherokee. So, perhaps the Blue Grass wasn’t

as much a result of raw nature as we once thought. For me

though, the message of blue grass as the aftermath of

anthropogenic land use was no t welcome news. However, evidence

for denser Native populations in central Kentucky will be good

news for those who have maintained that the pre-settlement

landscape was anything but unsettled. I'm thinking of Tom Bonnicksen in

particular.

Bonnicksen’s thesis is that what we often think of as the

untrammeled pre-settlement landscape was, in fact, worked over

pretty good by indigenous peoples over several millennia.

Bonnicksen, a silviculturist, is clearly biased toward wide

scale indigenous land use. In his “America’s Ancient

Forests” Bonnicksen has strung together informative anecdotal

accounts of Native American land use practices that undeniably

add to our understanding of the nature of the landscape of the

1600s and prior. In this regard, Bonnicksen has rendered a

service. However, be advised that Bonnicksen believes that old

growth forests in our national parks, as well as the wilderness

areas in our national forests, are going to waste. He believes

pretty much in managing woodlands for timber come what may. But

enough about Bonnicksen.

In summary, McEwan has done valuable research on the ecology of

the Blue Grass region. His research and that of Kentucky

archeologists points unambiguously to fairly concentrated

numbers of indigenous people in pre-settlement times in the Blue

Grass region. This does not surprise me. Native peoples did have

a large impact on millions of acres of the eastern forest biome,

but they likely had minimal impact on millions of other acres.

Where the balance lies, I don't know. The true nature of the

pre-settlement landscape is a puzzle that may never be fully

solved.

Ryan McEwan’s presentation was

followed by an animated and entertaining presentation by Jeff

Stringer, a silviculturist, who enlightened us on

“Silvicultural Methods to Enhance Old Growth Attributes in

Eastern Deciduous Forests”. Jeff definitely thinks in broader

and longer planning terms than does the industrial arm of

forestry. The latter has virtually destroyed any otherwise

legitimate claims forestry might have had as custodians of our

forests.

I acknowledge that

silviculturists like Stringer know a lot about forest structure,

and given the threats to our forests, they have important

contributions to make, especially when diseases and insect pests

threaten species after species. They may need to be at the

forefront of the efforts to hold on to at least some of the

attributes of what many of us cherish in our native forests. So,

I guess I need to support their efforts to give us designer old

growth - uh, to a degree. Since Stringer issued plenty of

caveats to his work, I wasn’t inclined to challenge him. His

presentation was a valuable contribution to the conference.

After a break,

my old friend Rob Messick gave a highly informative presentation

on the forest ecology icons of Kentucky past. Dr. E. Lucy Braun

ranks #1 of course. Although only a tiny fraction of the human

race knows who E. Lucy Braun is, she is a true giant among women

struggling to break though an old boy network.

Rob cited other

early scientists and foresters who showed a remarkable grasp of

the importance of preserve the remaining old growth forests on

public lands. His thesis was that there was a lot more knowledge

circulating around about the nature and whereabouts of OG than

subsequent generations have understood. I hope Rob will write a

book on the early forest icons. But what happened? In a

nutshell, with the advent of World War II and the national need

for timber, the Forest Service became a very different kind of

governmental agency. Control of the forestry profession passed

to an industrial-academic-government coalition that turned deaf,

dumb, and blind to the role and importance of retaining reserves

of natural forests. Authors such as Michael Frome (sp) have

written convincingly about the sub version of the Forest Service

during and after WWII. More recently, with the advent of the

environmental movement of the 80s and 90s, enormous pressure was

exerted on the Forest Service to re-connect to its original charge and substantial changes

resulted, with some excellent results. Don Bragg speaks

convincingly of the quality of forests on some of the national

forests. The big point is that Rob Messick has fashioned a

mid-life career out of this story. I hope he sees the project

through until a conclusion.

What emerged for me from Marc Evans’s presentation was a much

clearer picture of Kentucky’s natural heritage. Many people

visual oceans of blue grass and aristocratic horse racing when

Kentucky is mentioned. Song-writer Stephen Foster’s “My Old

Kentucky Home” induces a mild case of nostalgia in many of us,

but Kentucky is much, much more. It is naturally rich with flood

plain forests and the all-important mixed mesophytic zone. And

surprisingly enough, Kentucky offers many opportunities for

modest old growth discoveries. Its big trees, natural diversity,

cultural heritage, geological wonders (Mammoth Cave), old

growth, will keep some of us occupied for years.

After

a walk down through Hemlock Gardens followed by a very good

dinner, we returned to the evening session. For me, the

presentation by Marc Evans who carries the title “Community

Ecologist of the Kentucky Kentucky State Nature Preserves

Commission” was most illuminating. This Kentucky program

reminded me of an effort in Massachusetts back in the mid-1990s

to establish nature preserves. The MA program never worked. The

Massachusetts Bureau of Forestry wanted full control of all

forests on DCR lands and literally sabotaged the program. It was

a classic example of a turf battle that did not serve the common

good. But turf issues all too often govern the way our society

operates. Regardless, the Kentucky program is an example of a

red state program that trumps the efforts of a blue state. I

found this amusing, and having grown up in the red states,

satisfying to a small degree. But I don't take the feeling of

satisfaction too far. The horrendous destruction of the natur

al habitat and scenic beauty of Kentucky that the coal industry

has wrought speaks more to the composite impact of red state

versus blue state politics and mentality.

Lee

Frelich’s post-dinner presentation on the earthworm invasion

had a fresh face and was, as always, extremely informative. Lee

is an incredible engaging presenter. He knows how to take large

amounts of data, complicated relationships, obscure trends, and

draw clear conclusions for an audience of varying scientific

sophistication and do it in both a compelling and entertaining

way. He is simply one of the best presenters around. Other

highly qualified scientists often struggle with their

presentations. They never seem to know what makes for a good,

attention-holding presentation and what becomes insufferably

boring. How many planning steps and partial results must we have

to endure. I recall many groans from an audienc e trying to be

appreciative when exposed to one too may confusing graphs.

However, I’ve never heard anyone call Lee’s presentations

boring. His presentations not only get the highest marks for

informational content, but Lee's Garrison Keilor-like sense of

humor delights all but the stuff-shirts. In answering questions

from the audience, Lee is informative, but also blunt. He pulls

no punches, dodges no questions.

After dinner, we took a second walk in Hemlock

Gardens. Lee

and Neil accompanied us. I measured a huge chestnut oak. Jess

Riddle

took the girth at 12 feet and 2 inches. Its height to an obscure

crown

was right at 101 feet. Great tree? I look forward

to pitching in, exploring Kentucky, and helping out Neil in

whatever ways I can.

Well, I’ll stop here and pick up Saturday’s events in

Installment #4.

Bob.

|

| Installment

#4 |

Robert

Leverett |

| Jul

12, 2007 05:58 PDT |

ENTS,

Installment #4.

On Saturday morning Neil Pederson led off the morning program

with an

outstanding presentation, giving us a window into what we can

learn from

studying the tree rings. He illustrated how tree rings often

reveal

counter-intuitive information/trends. Rapid growth in old growth

trees

was an example that he gave. Neil stressed that in understanding

the

role that trees can play in our understanding of climate and

other

natural processes and phenomena. He reminded us that trees

record environmental events, probably in variety of ways yet to be

discovered. A life form that has endured for 400 or more seasons and bears

testament

to passing storms, fires, drought, wet periods, etc. is a life

form to

be respected and valued. The message was crystal clear.

Neil is a

superb presenter. He has an easy, comfortable style

of delivery. He knows how to emphasis points of real relevance

and

excites conference attendees over what is clearly his passion.

Neil is

extremely important to the old growth movement. I don’t mean

to

embarrass him with these accolades, but I hope Eastern Kentucky

University understands what an important researcher and teacher

they

have in Neil.

After

Neil, Dr. William Martin spoke to the management of old

growth mixed mesophytic forests. Bill is virtually an

institution among

old growth researchers. He is retired now and enjoying his

retirement.

In addition to being professor emeritus at EKU, for a number of

years,

Bill was the Commissioner For Natural Resources for the state of

Kentucky. In that capacity, he got an education on how hard it

is to get

the public to back good forest management, forest preservation,

and

sound environmental laws. Bill is a wily fellow with an

easygoing,

southern style of delivery, but his message packs a punch and

reflects

great experience. Bill has been the keynote speaker at a number

of old

growth conferences, including the one here in Massachusetts, and

in

Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and New Hampshire.

Over the years,

Bill has helped me in understanding a lot about

the essence of old growth ecosystems. He is of the old school

when it

comes to old growth definitions, in a "what you see is what

you get sort

of way". He shares his teaching burden of me with Lee

Frelich and

Charlie Cogbill. The three are very different in style, but all

are

powerhouses and have different contributions to make with

respect to our

understanding of old growth ecosystems. Each specializes in a

geographical region, but can take an expanded view when called

upon to

do so. There are other well-schooled old growth researchers,

some with

narrow focuses and some with broader ones. Looking at the group

as a whole, some will put you to sleep as lecturers and some are

exciting. A

few are spellbinding.

In my retirement

years, I have the hope of writing a book about

the modern academic shapers of our old growth awareness. I am

acquainted

with quite a few. We’ll see if I can follow through with my

desire to

tell their story.

At the end of

Bill’s presentation (I'll say more about his,

which dealt with management issues in a later e-mail), we had

lunch and

then headed for a real treat – an interpretive hike into

Blanton Forest. Our trip will be covered in installment #5.

Bob

Robert T. Leverett

Cofounder, Eastern Native Tree Society

|

| Installment

#5 |

Robert

Leverett |

|

Jul

12, 2007 15:00 PDT |

ENTS,

Installment #5

|

| Blanton Forest - photo by Carl Harting |

Blanton Woods OG was our field trip. The weather cooperated and

after

lunch on Saturday, we were on our way. The Blanton OG was

discovered by

Marc Evans back in the 1990s. I remember Bill Martin telling me

about

it. It turned out to be the largest OG reserve in the state. The

total

protected OG acreage in Blanton stands at about 2,300 although I

have no

doubt that Pine Mountain has more spots scattered over its

100-mile plus

length. Much of the OG is on the dry side of Pine Mountain and

it is

that side that we sat out to explore with Marc and Neil as our

very

capable leaders. After passing through a second-growth area, the

old

growth signatures became everywhere unmistakable - at least to

those who

recognize them. That apparently wasn't the case for Kentucky

state

foresters who flatly denied there could be any OG that they

didn't know

about when it was first reported by Marc. However, Bill Martin

quickly

put the issue to rest and Blanton has since grown into a source

of pride

for Kentuckians who are in the know. There is more to the

Blanton story

than that, but I'll leave the rest of it to Neil.

|

| Neal Pederson cores a nearly 300 year old white oak at

Blanton Forest - photo by Carl Harting |

We headed up Pine Mountain on a moderately steep trail.

Tuliptrees,

umbrella magnolias, hemlock, chestnut oak, and red maple caught

my eye. The rhododendron created that characteristic, slightly exotic

effect

that I associate with the southern Appalachians. We walked via a

path

that starts out in second growth forest. Well-shaped hemlocks

and

several impressive white oaks greeted us. I measured one to 105

feet in

height and 10.4 feet in girth. A second, discovered on the

return trip

measured 117.8 feet in height and 9.0 feet around.

|

| Marc Evans stands next to the recently christened (by Bob

Leverett) Marc Evans Hemlock in Blanton Forest - photo

by Carl Harting |

But to conclude, the trees on the dry side of Blanton forest are

impressive, but not overpowering. I measured the following

species

maximums:

Species Max

Hgt Max Girth Same

Tree

Hemlock 131.5 10.9

No

Tuliptree 135.3 7.4

* Yes

Red Maple 121.7 7.5 Yes

N. Red Oak 105.0 8.4 Yes

Chestnut Oak 105.1 9.7 No

* There are slightly larger ones, but the tuliptree performance

is not

at all exceptional for that species on the dry side of Blanton.

Marc

assured me that significantly larger tulips grow on the wet side

of the

mountain. I want to see them.

When Monica and I left Blanton, we headed down U.S. 25E passing

near

historic Cumberland Gap of Daniel Boone fame. Boone was a heck

of a

woodsman, but no better than the Indians who captured him. He

lived with

them for a year or more, as I recall, before leaving - sneaking

away, I

think. Anyway, we were passing through Daniel Boone territory.

We

entered Tennessee and rolled on, eventually crossing the Clinch

Mountain

Ridge at about 2,000 feet elevation. Serendipitously, we found

an

idyllic little cabin to spend the night. The cabin is perched at

the

edge of the mountainside overlooking a valley at about 1,000

feet below. The highest points of Clinch Mountain Ridge brush 2,500 feet, so

the

terrain has mountainous elements, but its long ridgeline

overlooking

smaller ridges and a large valley region gives it a different

feel form

the more continuous mountain terrain in the Pine Mountain

region. There

was something instantly pleasing about the spot and the cabin on

Clinch

Mountain.

The cabin had a small deck overlooking the valley beyond. By

opening

the front and back doors, a delightful breeze passed through,

and as

nightfall approached, Monica and I sat on the deck and looked

into a

starry sky. The night was magical, the stuff of novels. There

was

something else. On occasion, if one is lucky, one gets the right

combination of temperature, humidity, and breezes to experience

and

effect that is ineffable. Those were the conditions that we

experienced

that Saturday night. The little restaurant at the gap was

adequate, but

we chose not to eat there that evening. We both agreed that we

must

return to that spot on Clinch Mountain our next trip through

Kentucky

and Tennessee.

Still coming is our return trip

after the Smokies via the Blue

Ridge Parkway. I've already covered the Smokies portion. Oh yes,

I found

more OG in the Pisgah area along the Parkway.

Bob

Robert T. Leverett

Cofounder, Eastern Native Tree Society

|

| Re:

Installment #5 |

Neil

Pederson |

| Aug

06, 2007 08:42 PDT |

Bob,

Thank you for your excellent reporting on your trip and the

activities as a

part of the ENTS-Kentucky Old Growth Forest gathering. It was a

very good

time.

For those who has missed the meeting, you can download several

of the

presentations here:

http://people.eku.edu/pedersonn/kyOGentsmeet.html#presenters

Don't forget to miss Rob Messick's presentation that includes

several old

photographs/images of spectacular trees that were a part of the

original

forest in eastern Kentucky.

Bob asked me to say a few words on Blanton Forest, the primary

forest we

visited in southeastern Kentucky: http://www.blantonforest.org/

As Bob said, Blanton was 'discovered' [brought to the public's

attention] in

the early 1990s by state community ecologist Marc Evans. It is

amazing to me

that an intact forest of that scale could be discovered so

recently. I was

fortunate to be given permission to core trees in the forest to

reconstruct

drought history. I've cored in various sections of the forest,

mostly around

the upper slopes in the eastern portion, in a central portion

and in the

western portion of the reserve. There is just so many old and

large trees in

the forest. The undulating surface make the reserve seem so much

larger: *

http://tinyurl.com/26utgj*

- While leading a group of students across the

reserve from east to west while coring trees, it felt much like

that old

Simpsons episode where Bart keeps asking Homer how much further.

My

Homeresque reply as to when we'd get back to the one trail in

the entire

forest was, "Just over that next ridge." It was a

longer day in the field.

It was, however, a very productive day. I just made a quick

tally of the

trees cored. Of the 30+ [total] white & chestnut oaks, ~ 66%

are over 200

yrs [minimum tree age - no corrections for hollow trees or

distance to

presumed pith at coring height]. Nearly half of the total are

more than 300

yrs old. The oldest, a chestnut oak, dates to ~ 1669. Daniel

Boone wasn't

even thought of when this tree was moving to the canopy! We

cored around 16

eastern hemlocks as well. Many are at least 200 yr old [minimum

ages,

again], two are over 300 yrs. Many of the trees in both

collections were

partially rotten, too.

What I like about Blanton so much is that it is large enough to

'naturally

absorb' disturbance. A few of the large rock outcrops, like the

one that

caps the 70' Sand Cave, were burned over some time in the last

100 yrs, I'd

guess. The forest is recovering nicely - oaks, red maple and

other spp are

now in the sapling stage. Yet, if one moves just below or to the

side of

these burns, one can find old trees. It is a functioning forest!

At least it

was prior to the arrival of HWA, documented less than a yr ago.

It is a wonderful forest:

http://people.eku.edu/pedersonn/research/KYdrought/blanton/

See it when you can.

neil

|

|